With the Brexit transition period drawing to an end, this decision constitutes the last Community design case before the UK courts and represents a rare success story for a claimant in asserting infringement of a registered design.

In its decision, the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) found the registered Community design (RCD) for a pointed loafer shoe to be valid and infringed. Interestingly, it also concluded that the unregistered Community design (UCD), although valid, had not been infringed by the defendant’s ballerina shoe. This judgment helpfully explores the role of expert evidence in design cases.

BACKGROUND

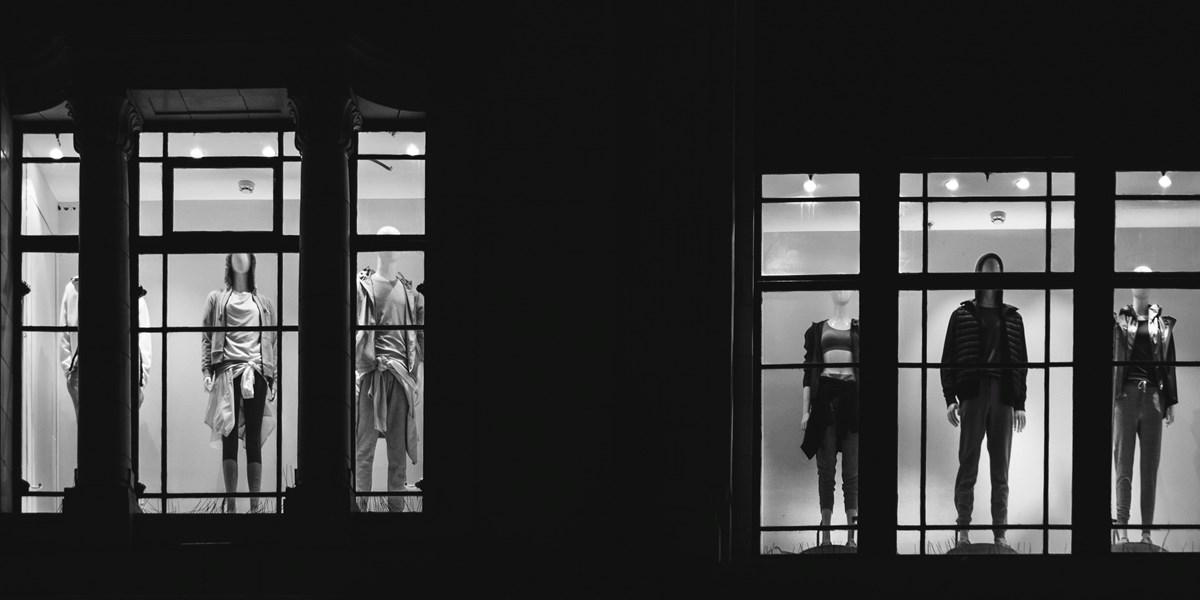

The claimant, a California-based shoe manufacturer, designed ‘The Pointed Loafer’ (depicted on the left below), a type of ballerina shoe with a pointed toe and a prominent tongue resembling a loafer. The defendant, an Austrian shoe company, began advertising a range of ballerina shoes online, which, importantly, included the ballerina shoe design the ‘Pointy Flat’ (depicted on the right below). The claimant issued proceedings against the defendant alleging that the Pointy Flat infringed its RCD and UCD. The defendant counterclaimed for invalidity of the RCD and challenged the subsistence of the UCD based on two prior designs.

The RCD was filed and registered on 9 November 2017 and includes seven views of the design (being the maximum number of drawings allowed by the EU Intellectual Property Office (the EUIPO)).

The UCD came into existence when images of the Pointed Loafer were first shared on the claimant’s website, in social media posts and in email exchanges with various individuals based in the EU. It is also noteworthy that the three-year UCD expired on 25 November 2020, shortly after trial but prior to this judgment. Therefore, if successful, the claimant would still be entitled to backwards-facing remedies such as damages and accounts of profits, although injunctive relief would not be available in respect of UCD infringement.

LIST OF ISSUES FOR DETERMINATION

Following concessions by the defendant on a few issues, the court was left to determine the following (the numbers corresponding to the List of Issues, which accompanied the CMC Order):

Design Corpus

- The state of the design corpus as at 10 May 2017.

Registered design

- Whether the RCD produces on the informed user a different overall impression from that produced by any of the prior designs.

- Whether the Pointy Flat produces on the informed user the same overall impression as is produced by the RCD.

Unregistered Design

- [conceded by the defendant].

- [conceded by the defendant].

- Whether the UCD produces on the informed user a different overall impression from that produced by any of the prior designs.

- Whether the Pointy Flat is an article which has been made by copying the UCD.

- Whether the Pointy Flat produces on the informed user the same overall impression as is produced by the UCD.

EXPERT EVIDENCE

The parties disagreed on the scope of expert evidence in this case, although it was agreed that expert evidence could be adduced in respect of issue 1 above. The court ordered that the parties might each rely on a single expert, whose reports might comment upon why a design feature relied upon is, or is not, part of the design corpus. Both experts’ reports exceeded this remit. Following correspondence concerning the inadmissibility of such evidence and an application by the claimant to adduce further evidence, a consent order was made by HHJ Hacon, pursuant to which the claimant filed a further statement in reply.

While allowing the evidence to be admitted, the judge (Mr David Stone, sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge) was critical of its expansive nature, determining that significant cost and court time could have been spared had the parties adopted a more focussed approach. He added that, when parties seek to benefit from the IPEC costs cap, they also agree to fit their case within the scope of the IPEC case limits and tailor their evidence accordingly.

In assessing the weight of the evidence in question, the judge considered key decisions of the Court of Appeal relating to expert evidence in design cases. Jurisprudence from Procter & Gamble, supported by the decision made in Thermos makes plain that expert evidence is generally of limited value in design actions. He made clear that parties and their lawyers should not jump to the conclusion that their case will necessarily be weakened by not adducing expert evidence. Ultimately, the most important factor in any such action is the appearance of the various designs. The judge commented that:

"That is an obvious risk of an elongated trial over-burdened with expert evidence on issues which are actually for determination by the court.”

Moreover, whilst the experts’ reports assisted the judge to "don the spectacles" of the informed user, he commented that submitting a brief primer would have achieved this more efficiently, and he did not consider himself bound by the conclusions drawn by the expert evidence, nor would he attribute it any weight in determining the issues. As such, parties, particularly in IPEC, should approach the issue of expert evidence with caution, and only seek to adduce such evidence where strictly “necessary and proportionate”.

The parties agreed that the interpretation of the RCD was a matter for the judge, as was the identity of the informed user, and the overall impression produced by the various designs and shoes.

With this in mind, the judge assessed the key design features of ballet shoes, such as the toe shape and heel height. He also considered the different materials from which the shoe could be made. It was agreed between the parties that there were no constraints on design freedom nor were there any elements of the designs solely dictated by technical function.

Regarding the RCD, the most important question of fact was the difference between the registration and the design corpus. Three points of interpretation arose in this case – the material of the upper, the perimeter of the topline and any asymmetry. Overall, the court held that the RCD produced a different overall impression on the informed user than that produced by the prior designs (shown below).

With respect to the subsistence of the UCD, the first disclosure, sufficient to found such a right, was held to have been appropriately evidenced by the claimant. Consistent with its reasoning in respect of the RCD, the court likewise considered that a different overall impression on the informed user would be produced by the UCD to that produced by the prior designs. Interestingly, the judge confirmed that the expert evidence established that the design of the upper was “unusual” and it seems that this did inform his view on validity.

The judge noted that the burden should not fall upon the defendant to prove that a design in the design corpus would have been known to the informed user. Simply, if the design is not held to be “obscure”, in that it would not “reasonably have become known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned”, then the design will be considered to fall within the design corpus and hence relevant for consideration.

INFRINGEMENT

In comparing the drawings of the RCD with the Pointy Flat, the judge concluded that, although differences in some measurements and ratios may be observed by the informed user, these were not significant to create a different overall impression, particularly given that the informed user was not a sectoral expert, but rather the ultimate user of the product. This led to a finding of infringement, and further commentary from the judge that a trial “over-burdened with expert evidence” ran the risk of the judge becoming “too expert” and hence not able to accurately consider the issue from the perspective of the actual informed user.

However, there was no finding of infringement in respect of the UCD; the available evidence did not establish copying by the defendant of the specific design in issue, being the Pointy Loafer, which must be proven in UCD actions (in contrast to RCDs). While the defendant had access to, and used for the purposes of product development, three of the claimant’s other shoe designs with very similar design features, the court was satisfied (at least on the evidence available) that it had not had access to the specific Pointy Loafer in issue.