In Focus

The UPC came into force on 1 June 2023. This means that Unitary Patents (UP) can now be granted by the European Patent Office (EPO), and the UPC has opened as a fully operational court, hearing a variety of actions across different divisions. The UPC has been a long time coming with several years of uncertainty. Although the UPC Agreement was first signed in 2013, the UK’s withdrawal in 2020 and three separate German constitutional challenges have all threatened the existence of the UPC.

UPs and the UPC are the most significant changes to the European patent system for several decades. Existing European patents, once granted by the EPO, are converted into a bundle of separate national patents which are subject to renewal, invalidation and enforcement on an individual basis in each territory. In contrast, UPs provide a single, uniform patent that covers 18 Member States who are participating in the UPC. Unitary Patents will be renewed by the payment of a single fee, as well as being invalidated and enforced centrally at the UPC. A fundamental feature of the UP system is that it is an “all or nothing” approach. This has the result that if a UP is revoked or lapses, it will cease to exist automatically across all member states; it cannot be in force for only some of the member states.

Current UPC Member States cover the majority of the European Economic Area with a population of over 300 million people and a GDP value of over $13 trillion. One UPC action will therefore cover a region exceeding the US market by population and GDP.

The ability to launch pan-European infringement and revocation proceedings through the UPC is therefore an extremely powerful tool for businesses, as can be seen by the recent decisions coming through the court.

The UPC has certainly been gaining momentum, following an initial period of nervousness surrounding the new forum and procedure.

The Court is proving itself to be a speedy and streamlined forum - whilst no full infringement or validity decision has been handed down by the court yet, the UPC has delivered rulings in respect of a handful of preliminary injunction applications within a few months, as well as showing willingness to grant injunctions ex parte where appropriate. The UPC Court of Appeal also delivered its first decision only one month after the grounds of appeal were lodged.

The UPC judges are, also, some of the most distinguished legal and technical personnel in Europe, which is being showcased by the well-reasoned and in-depth analysis, and with those judges applying valuable insights from their national practice. At the same time, judges appear to be taking a pragmatic approach when dealing with procedural issues, affording parties flexibility in the early days of the new Court, particularly when using the new Case Management System.

The UPC is, clearly, designed to be a front-loaded procedure. However, the rules do provide some flexibility in allowing expert evidence to be submitted at a later stage where appropriate. This has been welcomed by parties, giving the importance of filing a claim as soon as possible, with the risk of a patent being opted out at any time and with preparation of expert evidence often taking several months.

For more insights, please read more here.

The UPC has exclusive jurisdiction for all UPs granted under the new system.

Once a transitional period has expired (7-14 years), unless opted out, litigation of all disputes concerning national validations of European patents in unitary countries must be litigated in the UPC. During this transitional period, a patentee will remain entitled to take infringement cases before any of the national courts that are presently available to them.

Patents designated in countries which fall outside of the UP / UPC territories will continue to be litigated in the national courts.

Note that the jurisdiction of UPs is capable of expanding in the future with likely additions including: Ireland, Romania, Cyprus, Greece, Spain and Poland (with potential to allow for non-EU countries to sign up).

The UPC is made up of a number of first instance divisions, with all appeals being handled centrally at the Court of Appeal based in Luxembourg. The first instance divisions are split as follows:

The UPC Agreement prescribes the rules of where an action may be initiated and which particular court is competent to handle the case. For instance, an infringement action can be brought at the Local/Regional Division in the state the defendant is based or in any state where infringement is alleged to have taken place.

However, if the defendant is not resident in, and does not have a place of business in, a member state, and the member state in which the infringement occurred (or may occur) does not have a Local or Regional Division, then the action must be brought in the Central Division.

Revocation actions and actions for declarations of non-infringement will generally be heard before the Central Division, except where an infringement action between the same parties and concerning the same patent has been issued before a Local or Regional Division, in which case these actions must be commenced in the same Local or Regional Division as the infringement action.

The technical subject matter of the patent will determine which particular location of the Central Division has competence. The Central Division is seated in Paris (mainly focussing on patents concerning electronics, software, physics and SPCs), with a specialist division in Munich (mainly handling patents concerning mechanical engineering and chemistry). From June 2024, Milan will hear cases concerning human necessities. Whilst we await the Milan central division to commence (which is to replace the initially planned London seat), the responsibilities of this division are divided between Paris and Munich.

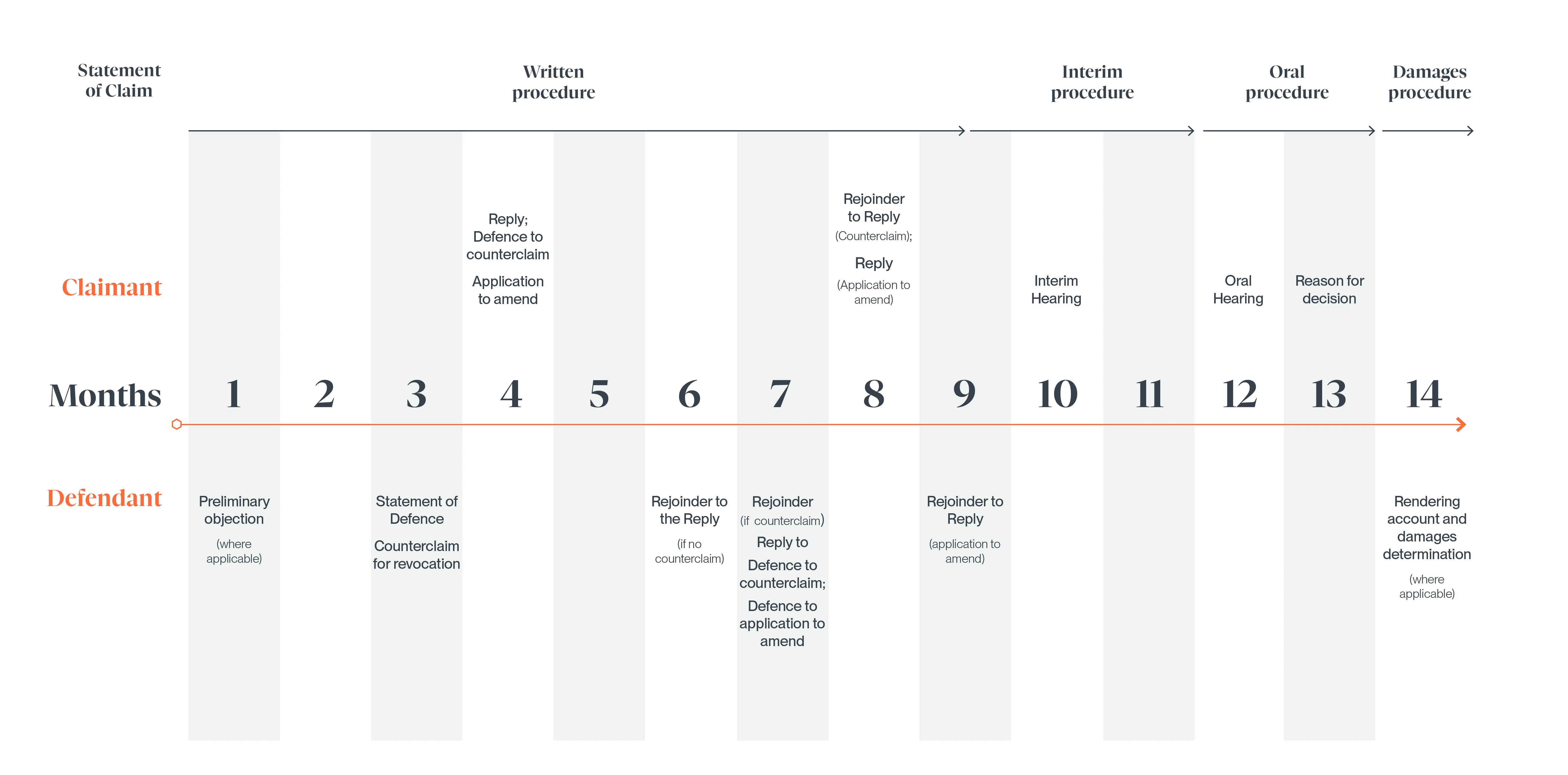

For both revocation and infringement actions, the UPC aims to reach a first instance decision within 12 months of commencement of proceedings, significantly quicker than when parties can expect to obtain an outcome in national actions (e.g. 18 months - 2 years before the UK High Court).

The UPC offers a front-loaded procedure, with facts and evidence filed at the “written procedure” stage with tight timeframes set under the UPC rules to respond to argumentation.

There are three key stages of the UPC procedure:

The below timeline sets out the likely timescales for an infringement action (although the pleadings differ for revocation claims, similar timeframes apply):

The written procedure allows for several rounds of submissions by the parties.

Within one month following a Statement of Claim or Statement for Revocation being filed by the Claimant, the Defendant may lodge a so-called Preliminary Objection, in order to challenge the competence of the UPC to hear the case or the language of the pleadings. Such objection is to be determined by the judge as soon as practicable.

Each case before the UPC is promptly assigned to a panel of judges (or a single legally-qualified judge, if requested by the parties). The panel will be comprised of technically and legally-qualified judges, which shall vary according to the Division hearing the case. Each panel will include a presiding judge (determined according to seniority) and a legally-qualified judge who assumes the role as the judge-rapporteur and will primarily be responsible for case management.

Following the end of the written procedure, the interim procedure will commence. This is primarily a case management stage, the aim being to make all necessary preparations for the oral hearing.

At this stage in the procedure, the judge-rapporteur may convene an interim hearing - held, where practicable, by telephone or videoconference.

The judge-rapporteur will identify the main issues, determine the relevant facts in dispute and establish a schedule for the remainder of the proceedings. The judge-rapporteur may also:

The oral hearing (see below) is set to take place around two months after the close of the interim procedure.

The trial (simply referred to as ‘oral hearings’ in the UPC rules) is held before the panel of judges, under the control of the presiding judge, and is typically concluded in one day in total (in contrast to national proceedings where infringement trials can last months).

The oral hearing consists of:

Under the control of the presiding judge, the parties may also put questions to the witness or expert.

The oral hearing (and any separate hearing of witnesses ordered) shall be open to the public unless the Court orders that the hearing should remain confidential, either in the interests of a party, any third parties or in the general interests of justice or public order.

The Court endeavours to issue its decision in writing within six weeks of the oral hearing - alternatively, the UPC may give its decision immediately after the closure of the oral hearing and provide its reasons on a subsequent date.

An appeal against a decision of the Court of First Instance may be brought before the Court of Appeal within two months of the date of notification of the decision. Orders can also be appealed within 15 days of being granted permission to appeal.

On appeal, the Court of Appeal will review the decision or order of the Court of First Instance in relation to the aspects of the decision or order contested and the reasons for setting aside the contested decision or order advanced by the Appellant. Requests, facts and evidence which have not been submitted by a party during proceedings at First Instance may be disregarded by the Court of Appeal.

The Court of Appeal may also, in some circumstances, determine issues that the Court of First Instance failed to decide but which it considered necessary to decide on appeal. Only in exceptional circumstances will the Court of Appeal refer a matter back to the Court of First Instance for retrial. Decisions of the Court of Appeal cannot be subject to further appeals.

There are three stages to appeal proceedings - written, interim and oral – which are broadly similar to those in first instance proceedings. Note, however, that there is no provision in the UPC Rules of Procedure which indicates when an appeal should be heard or when a subsequent decision will be issued by the Court of Appeal.

An appeal will not have suspensive effect unless the Court of Appeal decides otherwise at the request of a party, with the exception that an appeal against a decision on actions (or counterclaims) for revocation will always have suspensive effect.

An application for provisional measures may be sought from the Court as a form of quick judicial relief and is often granted within only a few days of making the application for such relief.

Provisional measures available under the jurisdiction of the UPC include:

Such measures may be awarded where the Court deems appropriate, taking into account the urgency and the interests of the parties including any potential harm resulting from the granting or refusal of the provisional measure.

Provisional measures may be useful in providing speedy relief for patent holders. However, it is important to seek considered advice before lodging any application. For example, the Court may order the applicant to provide security to compensate for any injury which may be caused to the defendant in the event that the provisional measure should not have been awarded. Apart from in exceptional circumstances, such security is required to be paid by the applicant when the provisional measure is ordered ex parte (i.e. without the defendant having been heard).

Firstly, decisions and orders are enforceable across all UPC Contracting Member States, save that those concerning non-unitary patents are only enforceable in the jurisdictions in which the patent is validated. Enforcement takes place in accordance with the same rules and laws as decisions issued in the respective Contracting Member State.

A wide range of interim and final remedies are available across all 18 Contracting Member States. Interim remedies can be sought at various stages of the case or even before an action has commenced. Final remedies are available following a substantive decision on the merits of the case. The interim and final remedies available include:

For infringement actions, UPC court fees comprise of a flat fee of EUR 11,000 + a value-based fee for actions valued greater than EUR 500,000. A value-based fee will be charged in respect of the following actions:

The below table sets out the applicable value-based fee, based on the estimated value of the action:

In contrast, the fee for a revocation action is fixed at EUR 20,000, regardless of the value of the matter under dispute. The fees for all other actions are set out below:

For multi-party/multi-patent actions only one set of such fees applies.

Importantly, SMEs will be entitled to up to a 40% reduction in court fees. Furthermore, there will be reimbursements of fixed and value-based fees of up to 60% for cases which settle early, for withdrawal of an action or where only a single judge hears the case.

Like most European national systems, the UPC provides cost reimbursement claims for the successful party of an action, to the extent that such costs are reasonable and proportionate.

There is, however, a sliding scale of recoverable costs for representation in the UPC, depending on the value of the claim (up to a maximum of €2 million for claims valued over €50,000,000) as set out in the below table. This applies equally to revocation actions as it does to infringement claims. Parties may request to lower the ceiling if, in the event that the requesting party is unsuccessful, the amount of recoverable costs of representation to be awarded to the successful party would threaten the economic existence of the requesting party (particularly pertinent for SMEs, public bodies and universities). Parties may also request the ceiling is raised, particularly for complex cases. The ceilings for recoverable costs are set out below.

UPC Evidence and burden of proof (vossius.eu)

The UPC Agreement sets out a lengthy list of evidence that parties can utilise in support of their case in UPC proceedings. This non-exhaustive list includes hearing the parties, requests for information, production of documents, hearing witnesses, opinions by experts, inspections, comparative tests or experiments, sworn statements in writing (affidavits). A party may provide written witness statements as well as written expert opinions in proceedings. However, they may also request that a witness and/or expert be heard in person (or this could be ordered by the Court on its own motion).

Although a front-loaded procedure, the UPC rules allow claimants to submit evidence at a later stage in the written procedure (provided they have indicated so in their initial Statement of Claim), giving parties an opportunity to review the arguments raised in the defence before finalising this.

Cross-examination of witnesses and experts is not available automatically, but could be ordered where, and to the extent, considered appropriate by the Court (in contrast to UK patent proceedings, where cross-examination takes place by default).

Additionally, if the UPC considers that the evidence presented by the parties is insufficient to assist it in resolving a dispute, the Court may obtain additional evidence through the appointment of a Court expert.

Further evidence may also be obtained through investigative measures, where permitted by the Court, such as an order to produce or preserve evidence and/or to inspect premises in order to establish infringement. Before ordering a party to produce evidence, that party has the opportunity to be heard. To obtain such order for preservation or inspection, the claimant must provide evidence to support the claim that the patent has been infringed or is about to be infringed. Once the Court grants this request, the measures may be conducted before proceedings are commenced or during proceedings. In order to guarantee the full effectiveness of this measure, the order can be obtained ex-parte. This means of obtaining evidence is similar to the saisie-contrefaçon procedure available in France.

Language Regime in UPC Proceedings (vossius.eu)

Generally, the language within the Court of First Instance is the official language of the Contracting Member State hosting the Local Division or the official language designated by the Contracting Member State sharing a Regional Division.

For reference, please see the below table setting out the designated languages for each division. As there is more than one language designated in most divisions, the claimant has the right to choose the language of proceedings subject to limited exceptions.

Infringement proceedings can be brought in English in all the Local or Regional Divisions.

The language used in the Central Division is the language in which the patent is granted. With the majority of patents being granted in English, many proceedings before the Central Division will be heard in English.

The language used in the Court of Appeal is the language of proceedings before the Court of First Instance. However, the parties may agree to use the language of the patent instead.

In most cases, every document will need to be translated into the language of the proceedings. Whilst these translation costs are covered by the party submitting the document, they may ultimately be paid for by the losing party.

At the request of the defendant or the Court, the proprietor may be required to provide a full translation of the patent in dispute.

In addition, at the request of a party, interpretation facilities will be provided to assist the parties at any oral proceedings.

Note that the language adopted in the statement of claim can be objected by the defendant within one month of service of the statement of claim (i.e. as a preliminary objection).

The European Patent with unitary effect, or Unitary Patent (UP), is a single right that covers all of the participating Member States of the European Union. The new UPC handles enforcement of a UP throughout the participating Member States.

A UP may be designated from any EPO application as it proceeds to grant. The participating Member States that are covered by a UP are:

Notably, Spain, Poland and Croatia are not participating in the UPC despite having the opportunity to do so being Member States of the EU. These states may join the agreement later, but for now European patents will need to be validated directly in these states if they are of interest. Of course, the UK is also not participating in the unitary system, having now left the European Union.

A UP is a single right that covers all participating Member States, and for which only a single annual renewal fee is payable.

In addition, a single court decision, e.g. on infringement and/or validity, applies across all participating Member States rather than just in one country.

Patentees are therefore be able to bring a single infringement action for pan-European infringements, while third parties are able to seek centralised revocation of the Unitary Patent.

Unitary Patents are also subject to revocation via the EPO opposition procedure.

The introduction of the UP and UPC does not immediately supersede the existing framework for European patents, which will continue to be available from the EPO. Instead, the UP is an alternative patent issued by the EPO for EPC Member States which are part of the EU and have signed and ratified the UPC Agreement.

Patent coverage across all EPC Contracting States can therefore be achieved by a European patent validated in national states (as is currently the case) or by the combination of a UP with a European patent validated in non-UP Member States.

When a European patent application proceeds to grant, applicants therefore have the following options:

It is anticipated that the unitary system will ultimately supersede the present system, but it seems unlikely that this will happen anytime soon. There will at the very least be a seven years transitional period, which may be extended to fourteen years. Further, with several states not part of the unitary system, but included within the current system, there are some major changes and decisions that would be required for this to eventually happen.

The EPO is responsible for the procedure to obtain a Unitary Patent. There are two basic requirements that must be fulfilled before a UP designation can be obtained.

Firstly, in order to be eligible for a UP, a European patent must have the same claims in all participating Member States. It is therefore not possible to obtain a UP from a European patent that has different claims in one of the participating Member States, for instance in view of national prior rights that may exist.

Secondly, the European patent must grant with the designation of each of the 24 participating Member States still being valid (i.e. the designation should not have been withdrawn during prosecution).

Providing both requirements are met, the UP designation must be filed at the EPO within one month of the mention of grant of the European patent being published in the European Patent Bulletin.

For a transitional period, there is also a requirement to file a translation of the full specification into English (if the official language is French or German), or alternatively into any other official language of the EU where the official language of the proceedings is English.

Once the UP has been designated, it is then not possible to validate the patent in any of the participating Member States as a national designation.

Providing these requirements are met, it will be possible to obtain a UP from any European patent that proceeds to grant. It is however not possible to retroactively convert granted European patents having validated in the participating Member States to a Unitary Patent.

The costs for a UP are significantly lower than the total costs of the national patents that it replaces.

The validation formalities initially only require the full specification to be translated into one other language (this formality is only for a transitional period), and there will no longer be a need to provide a local address for service in the participating Member States.

The ongoing costs for renewals are expected to represent the equivalent of the national renewal fees for the four most common validation states. The UP is therefore be a more cost effective option unless only a few states are of interest.

The ongoing administration of a UP also presents advantages, as the single right has a central register corresponding to all 24 Member States. Transfers and other recordals will therefore be easier to administer. This does however present some limitations, such as the inability to strategically drop part of the portfolio covering Member States at a later stage to reduce the cost of annuities.

In principle there is no reason why a UP cannot be used as the basic patent in support of an SPC. The SPC Regulations (Regulation EC No 469/2009 for medicinal products and Regulation EC No 1610/96 for plant protection products) do not limit the origin or type of patent that can be used as the basic patent for an SPC, and only require that it must protect the product in the territory for which the SPC is being sought. The fact that the basic patent may simultaneously protect the product in several territories should not affect the ability for the patent to support SPC applications in those territories individually.

The European Commission’s website also states that it is investigating the wording of the legislation to ensure that it will not be a problem to use a European patent with unitary effect as the basis for an SPC.

The future possibility of the creation of a ‘unitary SPC’ would require the selection or creation of an institution that would examine and grant this new right. Unlike for the creation of the European Patent with unitary effect, for which the necessary infrastructure was largely in place through the EPO, an appropriate solution for ‘unitary SPCs’ is less obvious. Nevertheless, the Commission has announced an intention to propose new legislation for having a single procedure for granting SPCs (potentially via the creation of a new 'unitary SPC'), although it has not yet provided details of its proposals or opened a call for evidence (see our article here).

The UP clearly represents a cost effective route for obtaining patent protection across all 18 participating Member States. It can therefore be expected that patent holders typically only validating in a few states may choose to use the UP to obtain much more far reaching patent protection for the same cost.

This may in turn impact the freedom to operate of businesses having operations in the EU that have developed a strategy to avoid their competitors' typical validation strategies.

It cannot necessarily be assumed that there will be general use of the Unitary Patent, despite the clear cost savings that it represents. The uncertainty of how the UPC will operate may lead businesses with extremely valuable patent assets to opt for traditional national validation strategies while the ability to opt-out of the UPC is still available, even if this route is more expensive. Moreover, there may be an increased use of national filings in key jurisdictions to avoid patent rights ever falling under the jurisdiction of the UPC once the transitional opt-out period has expired.

The UP is also a single right, meaning that it must have the same owner(s) for all participating Member States. This may impact how multinational companies handle their patent portfolios post grant, requiring the rights associated with each of the participating Member States to be handled via license agreements instead of assigning the rights to different entities.

Overall, the decision on whether to opt to obtain a UP will depend on a number of business and commercial factors, way beyond simple cost considerations.

All European patents with unitary effect (that is, Unitary Patents) must use the UPC for infringement or invalidity proceedings. This is not the case for European patents that are validated in a participating Member State, whether granted before or after the UPC comes into force.

For a transitional period of at least seven years, such nationally validated European patents (and any Supplementary Protection Certificates based on such patents) will fall within both the jurisdiction of the national courts of the relevant Member States, as well as the UPC.

However, for nationally validated European patents (and any SPCs based on the patent) it is also possible to “opt-out” of the UPC by filing an opt-out request. The opt-out request can be filed at any time up to one month before the end of a transitional period, which will last for an initial period of seven years and may be extended for up to a further seven years. The filing of an opt-out request will have the effect that any infringement or invalidity proceedings must be handled by the national courts, just as they are now, and it will not be possible to start such proceedings before the UPC. The application to opt-out a nationally validated European Patent extends automatically to all SPCs based on the patent, and moreover if any SPC is granted after the application to opt-out, the opt-out automatically takes effect on the SPC when the SPC grants.

It is important to note that any request to opt-out a nationally validated European patent (together with any SPCs) must be made before any proceedings are started at the UPC. For example, if invalidity proceedings are started at the UPC by a third party before an opt-out request is filed, it will no longer be possible to opt-out of the UPC and the European patent (and any SPCs) will be within the UPC system for the remaining lifetime of the patent.

If a nationally validated European patent is opted-out, this prevents a central invalidity attack on the patent at the UPC. A successful central invalidity attack at the UPC would have the effect of revoking the patent in all member states of the UPC and opting-out prevents the possibility of this.

An opt-out request can be withdrawn later. That is, it is possible to opt back in to the UPC. This can be done at any time but only if infringement or revocation proceedings have not been started at any time in a national court. This includes any proceedings that were finished or withdrawn before the UPC came into effect. If a European patent (and any SPCs) is opted back in to the UPC, it is not then possible to opt-out again. In other words, it is only possible to opt-out once.

The sunrise period was available to opt-out nationally validated European patents before the UPC took effect. Opting-out during the sunrise period had the effect that invalidity actions could be started at the UPC immediately when the UPC came into effect. Despite the sunrise period ending, nationally validated European patents (and any SPCs) can continue be opted-out at any time up to one month before expiry of the seven-year transitional period (unless proceedings have been started before the UPC).

After the seven-year transitional period (which may be extended by up to a further seven years), all nationally validated European patents (and any SPCs) that have not been opted-out, must use the UPC. This will include any nationally validated European patents granted on applications filed after the expiry of the transitional period (and any SPCs based on them).

.webp)

Published European patent applications can also be opted out of the UPC before grant. The result of this is that it will not be possible to use the UPC to centrally invalidate national validations of the European patent for participating member states when it is granted. However, it will still be possible to oppose granted European patents (and Unitary Patents) at the EPO.

Opting out pending applications may be helpful because the Court has not yet ruled on the possibility that third parties seeking to avoid patent infringement can file “Arrow” declarations and thereby draw pending applications into proceedings before the Court. “Arrow” declarations have become increasingly popular in certain jurisdictions, including the Netherlands and the UK, and the UPC’s appetite remains unclear.

The decision of whether or not to opt-out should be factored into the ongoing management of a portfolio of European patents.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%203.jpg)