In the latest development in the intellectual property fight between Lidl and Tesco, the Court of Appeal has overturned a High Court ruling to strike out Tesco’s bad faith counterclaim. We can now expect the Court to consider whether Lidl’s actions constitute bad faith by repeatedly filing the same mark (‘evergreening’), where the mark may have been obtained for the purpose of bringing legal proceedings, and despite it not being registered strictly in the form that it is used.

WHAT IS THE DISPUTE?

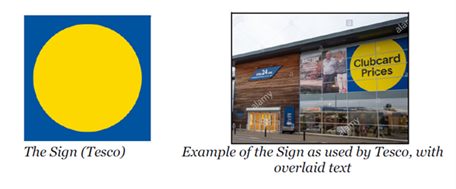

To recap previous proceedings, Lidl sued Tesco in 2020 shortly after Tesco started using a yellow circle against a blue background (the “Sign”) to promote its ‘Clubcard Prices’ scheme:

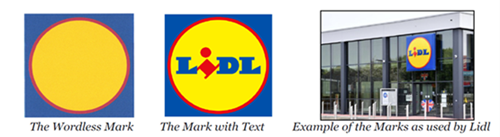

Lidl claimed that Tesco infringed its registered trade marks (the “Wordless Mark” and the “Mark with Text”). The Wordless Mark is a yellow circle with a red border on a blue square background without text, and the Mark with Text is identical but for text reading ‘LIDL’ within the circle. Tesco’s ‘Clubcard Prices’ Sign is very similar, being a yellow circle on a blue square background:

Lidl alleged trade mark infringement under sections 10(3) and 10(4) of the Trade Marks Act 1994, as well as passing off and copyright infringement. Interestingly, Lidl argued that Tesco sought to take advantage of its reputation as a ““discounter” supermarket known for the provision of value”.

BAD FAITH ALLEGATION

Lidl’s complaint about Tesco’s use of The Sign (which does not include any text) was met with counterclaims including for invalidity of six of Lidl’s registrations for the Wordless Mark on the grounds of their registration in bad faith. Lidl’s arguments on bad faith included that:

- The Wordless Mark is a “legal artifice” that has never been used by Lidl as registered;

- There was no bona fide intention to use the Wordless Mark as registered;

- Lidl applied for the Wordless Mark “solely for the purposes of deployment as a weapon in legal proceedings”;

- Lidl made further applications for the Wordless Mark to circumvent the non-use periods (i.e. ‘evergreening’); and,

- Lidl made the applications purely to obtain a monopoly right.

STRIKE OUT APPLICATION

Prior to trial, Lidl applied:

- to strike out the bad faith allegation in Tesco’s counterclaim; and

- for permission to rely upon survey evidence at trial.

In an interim decision Mrs Justice Joanna Smith agreed with Lidl that the allegation of bad faith did not have a realistic prospect of success and struck it out. Tesco appealed, leading to this decision.

THIS APPEAL

The decision can be found at: Lidl Great Britain Ltd v Tesco Stores Ltd [2022] EWCA Civ 1433.

Tesco raised the following two grounds of appeal, arguing that the judge failed to:

- apply the correct test for strike out under CRP 3.4(a) and/or to consider the fact that bad faith is a developing area of law; or to

- consider the bad faith counterclaim as a whole.

Arnold LJ considered only the second ground of appeal to be well-founded. He deemed the allegation that the Wordless Mark was filed purely as a legal weapon a permissible inference from the facts that had not been refuted by Lidl. If anything, Lidl had supported the inference by admitting that “the Wordless Mark was applied for to expand monopoly rights”.

Further, Arnold LJ acknowledged that filing for an unjustifiably broad scope of protection may amount to an abuse of the trade mark system and therefore bad faith. However, he stated that the question of whether such a strategy amounts to bad faith is fact-sensitive. In this case, Lord Justice Arnold found that Tesco’s statement of case pleaded sufficient objective indicia to give rise to a real prospect of the presumption of good faith being overcome - Tesco had succeeded in shifting the evidential burden to Lidl.

Regarding Tesco’s claim of ‘evergreening’, Arnold LJ found that sufficient particulars had been given to support the allegation and therefore concluded that the plea had a real prospect of success.

Consequently, the court found that the bad faith counterclaim had a real prospect of success and allowed the appeal, reinstating the allegation of bad faith. A full trial was heard at the High Court in February 2023, with a report of the decision found here.

TAKEAWAYS

This case reminds us of the high hurdle for strike out applications and potential difficulties in pleading bad faith. To avoid strike out Tesco had to show a realistic prospect of success, not that it would actually win at trial. Here, Tesco was able to discharge this burden, despite the fact that bad faith allegations also have a high threshold to meet. Indeed, Lord Justice Arnold thought that there was “sufficient objective indicia to give rise to a real prospect of the presumption of good faith being overcome so as to shift the evidential burden to the applicant for registration to explain its intentions”. Reversal of Smith J’s striking out of the allegation of bad faith suggests clarity may be on the horizon over an issue that has become hotly contested and increasingly relevant in forming filing strategies.

The issue of genuine use may also raise an interesting conundrum for Lidl: Tesco’s allegation of bad faith filing of the Wordless Mark may be contingent on whether the court finds that use of the Mark with Text also supports use of the Wordless Mark. As a discounter whose business model relies on lookalike, own-brand products, for Lidl to successfully fight the counterclaim for invalidity, it may have to argue that a ‘lookalike’ is not adequately differentiated from an existing product or get-up by the addition of a different brand name or word. This is a potentially very uncomfortable argument for Lidl to make.